Can you and should you time the market?

“It’s not about timing the market, but about time in the market,” investors with a well-diversified portfolio tend to do better than those who aim to profit from trying to predict market turning points.

Written by Steve Davies, CEO of Javelin Wealth Management

The list of investors who claim to have perfect foresight as to market moves is long and often infamous (“even a broken clock is right twice a day”). We don’t plan on joining that list, so we revert to looking at market history and seeing what we can learn from previous cycles. Even if “past performance is not an indicator of future returns”, that history can still provide valuable perspectives.

Understandably, volatile markets make people nervous: we’ve had a good dose of that in 2022 and 2023. After an almost 18% fall in 2022, the S&P 500 recovered by the same amount by July 2023, before giving back half of that in the months since then. The finger of blame has been variously pointed at inflation, too-hawkish central banks, an anaemic global economy, political disfunction in large economies, and, most recently, “geopolitical tensions” (otherwise known as “war”). However, even if we know that past performance is not an indication of future returns, that doesn’t stop “repeated patterns of irrationality, inconsistency and incompetence in the ways that human beings arrive at decisions and choices when faced with uncertainty”. The author of this quote, Daniel Kahneman, (a psychology professor at Princeton in the early 2000s) also points to the fact that investor behaviour often differs from logic due to the instincts of the herd.

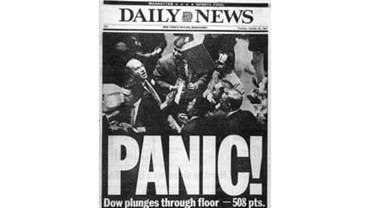

[Source: New York Daily News, 20th October 1987]

To be objective, investors have good reason to feel nervous, when that herd instinct takes over, the falls can be sharp and painful. There have been five major crashes in the last 40 years alone and that’s not counting a number of smaller or shorter ones, each of which led to “corrections” of 10% or “bear markets” with declines of 20% or more.

| 1987 The October Crash |

| 1997 The Asian Financial Crisis |

| 1998 The LTCM Russian collapse |

| 2001 The Bursting of the Dot Com Bubble |

| 2008 The Global Financial Crisis |

Without the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, should it have been possible to predict these major events before they happened? It is never an easy ride on the way up in a bull market: it’s called the “wall of worry” for a reason. Investors seem perpetually distressed, worried about the valuation levels, forever peering around the next corner – ever watching for the canaries in the coal mine that might signal the onset of the next market downturn. More often than not, though, these only ever seem obvious after the event: the supposed guru who “called” the 1987 October Crash had actually said the same thing every year for the previous 5 years, during which – prior to the crash – the market rose by 145% (still up 72% post-crash).

Whilst it’s probably easier to spot longer-term trends, that becomes almost impossible over shorter periods. It is also not possible to predict the central banks and government’s policy responses. There is also the key point of how much bad or good news is already “in the price”. For example, in February 2009, things were still looking incredibly grim in the teeth of the Global Financial Crisis, but that was the moment that central banks started chanting their “we’ll do whatever it takes” mantra: it just took a while before a majority of investors started believing it. No one wanted to be guilty of catching a falling knife. But those knife catchers in February 2009 did well… in the following three months markets rose by 30%.

The next thing to bear in mind is the cost of not being invested when markets go up:

[Source: Investec]

The graphic shows that if you were invested the entire time between January 2003 and December 2022, you would have made twice as much as the person who missed those 10 best days by trying to time things perfectly. Note that 7 of those 10 best days took place in bear markets, proving perhaps that the darkest of clouds often have the silverest of linings.

The disparity widens on a longer term – an investment of only $100 at the beginning of 1900 would have turned into $25,746 by end 2006. Miss the best 10 days, however, and you would have returned a massive 65% less. So much so, that by missing the best 100 days in that 106-year period, the terminal wealth dropped by a staggering 99.7% to $83 (less than the initial capital invested!)

| 1900 to 2006. $100 starting investment | Terminal Wealth | Portfolio Value vs Staying Invested | Annualized Growth rate |

| Return if invested throughout | $25,746 | +5.3% | |

| Return if best 10 days missed | $9,008 | -65% | +4.3% |

| Return if best 20 days missed | $4,313 | -83% | +3.6% |

| Return if best 100 days missed | $83 | -99% | -0.2% |

[Source: “Black Swans & Market Timing; Estrada. IESE, November 2007]

To further prove my point, consider the scenario of having invested your money at the peak of each of the last five major market crashes. The answer is not as depressing as it seems. Looking at the S&P 500 and the MSCI World Index, if you had invested into a balanced portfolio consisting of 60% equities and 40% bonds at the peak of each market cycle, that portfolio would have outperformed cash substantially over the next 10-year period.

So, if there’s one call to action for long-term investors, it’s this: let your money do the work, whilst you sit back and relax. You’ll be happier that you did.

Note: This article was inspired by an earlier work from Alexandra Nortier, Joint-head Wealth Management at Investec.